Illuminance Meters, commonly referred to as light meters or lux meters.

In days of old, when tungsten filament lamps were the only light source to consider, light meters worked from a single sensing cell.

The cell was not particularly well matched to the CIE Photopic curve V(λ), but was calibrated to give the correct reading when measuring that particular light source.

The calibration light source was usually CIE Illuminant A which is similar to an incandescent lamp.

That was fine until different light sources arrived in the shape of fluorescent and HID lamps, each with their own different spectrum.

Light meters were then given a light source selection switch, usually marked Day, HPS, Fluoro, GLS etc.

The light meter was calibrated to give the correct reading when measuring the corresponding light source.

Laboratory spectrometers were used to measure the radiant power of light sources at each wavelength, which could then be weighted against the V(λ) curve.

Comparing the results for each type of light source against the calibration light source gave the fixed multiplication factors used by the light source selection switch.

This worked because the actual spectrum of each type light source was known in advance.

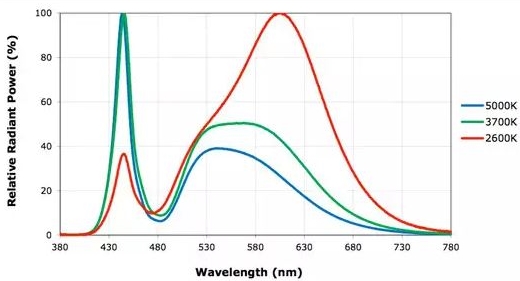

The problem with LEDs is that the Spectral Power Distribution (SPD) is not known in advance, and can vary widely.

Each different SPD would result in a different multiplication factor.

In the example above, the multiplication factor could vary from 1.06 to 1.23.

If you don’t know the spectrum you are measuring you cannot know the accuracy of your meter.

Using a single correction meter with an LED source can cause errors as high as 30-50%

Improvements in sensor technology resulted in light meters that ever more closely matched the V(λ) curve.

The meters however were still dependant on the single multiplication factor derived from the results of the expensive laboratory spectrometers measuring the differences between the SPD of light sources.

Years ago, spectrometers were lab instruments that cost tens of thousands of pounds, it was impractical to use such instruments on site, so the cheap light meter was born.

Nowadays you can buy a full spectrum analysing meter for around £1,000 which directly measures the SPD, and from this derives the true illuminance and other useful information such as CCT, CRI and S/P ratio.

Spectral Illuminance meters are not perfect, they have the same type of accuracy and repeatability problems as conventional meters, so don’t go thinking they are 100% accurate.

The old maxims remain true, you get what you pay for.

Cheaper meters will break the visual spectrum into 8 or 10nm intervals, while better instruments will go to 5 or 2 nm steps, the smaller the wavelength interval the better the meter.

There is much discussion in the measurement industry about actually defining and using an LED source to characterise the errors in LED measurement systems and this is generally seen as desirable.

Bodies such as the CIE are working towards an LED reference standard.

Cosine correction.

There is one other potential major source of error that is particularly prevalent in flood lighting and road lighting.

Simply put most light meter sensors are flat, so to give a true reading, measurements of light falling at high angles of incidence onto the sensing cell must be corrected by the cosine of the angle at which they enter, this is cosine correction.

A good light meter will always quote its cosine correction. Even a cheap meter with a flat opal filter as a cosine correction will be OK up to about 30 degrees with probably less than 5% error, but at 80 degrees it is easy to find meters that have a cosine error of 30%.

In interior situations the largest portion of the light entering the cell at angles where the cosine error is small.

In road lighting and flood lighting a large proportion of the light entering the cell is at angles where the cosine error can be significant and can potentially cause large errors in measurement.

In these cases measurement techniques must compensate for these errors.

Calibration

One final point, no matter how much or little money you spend on a light meter unless it is regularly calibrated it is completely useless.

Question: What do we call an out of calibration light meter?

Answer: A useless lump of plastic